Mechanical Wonders at the Louvre, From Ancient Egypt to Vacheron Constantin

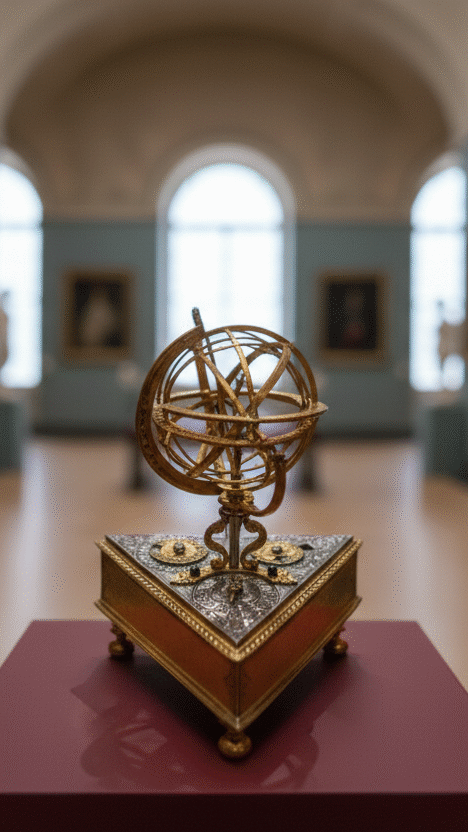

Mécaniques d’art, which opened on September 17th to commemorate the 270th anniversary of Vacheron Constantin, the museum’s philanthropic partner, is an exhibition at the Louvre dedicated to mechanical art objects, specifically ten historically significant clocks and watches (though some of the oldest are only fragments).

The exhibit, on display in the Sully wing until November 12th, shines a welcome light on an often-overlooked aspect of the museum’s decorative arts collection; pieces that merge technical expertise with mankind’s obsessive quest to measure time and explain the heavenly bodies.

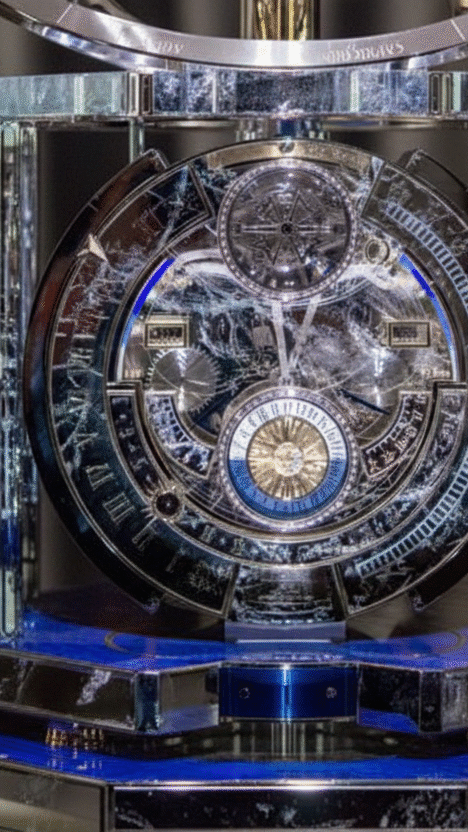

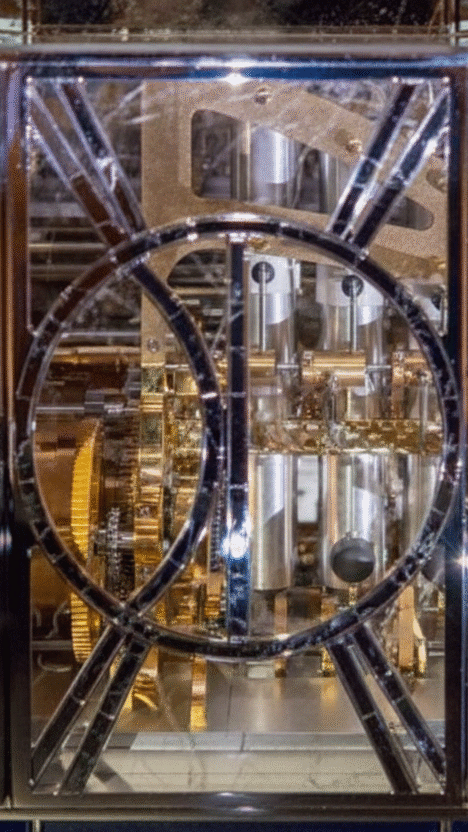

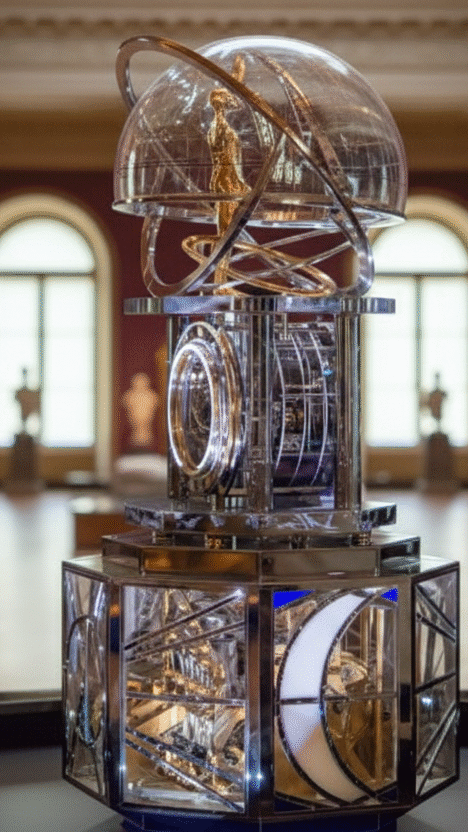

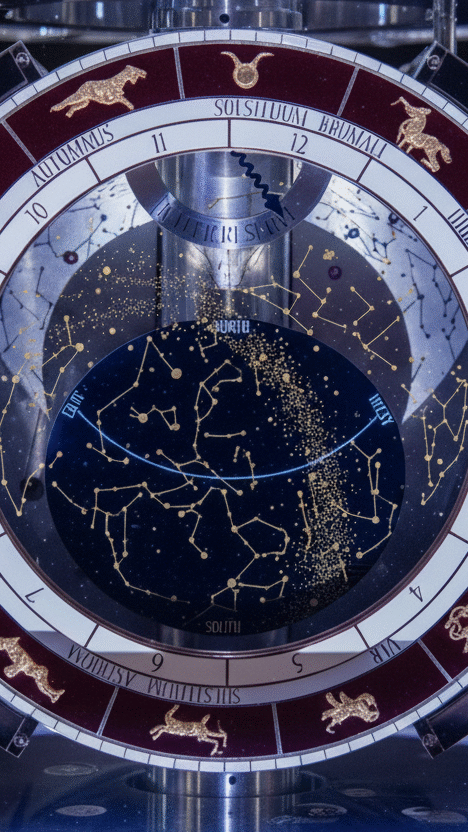

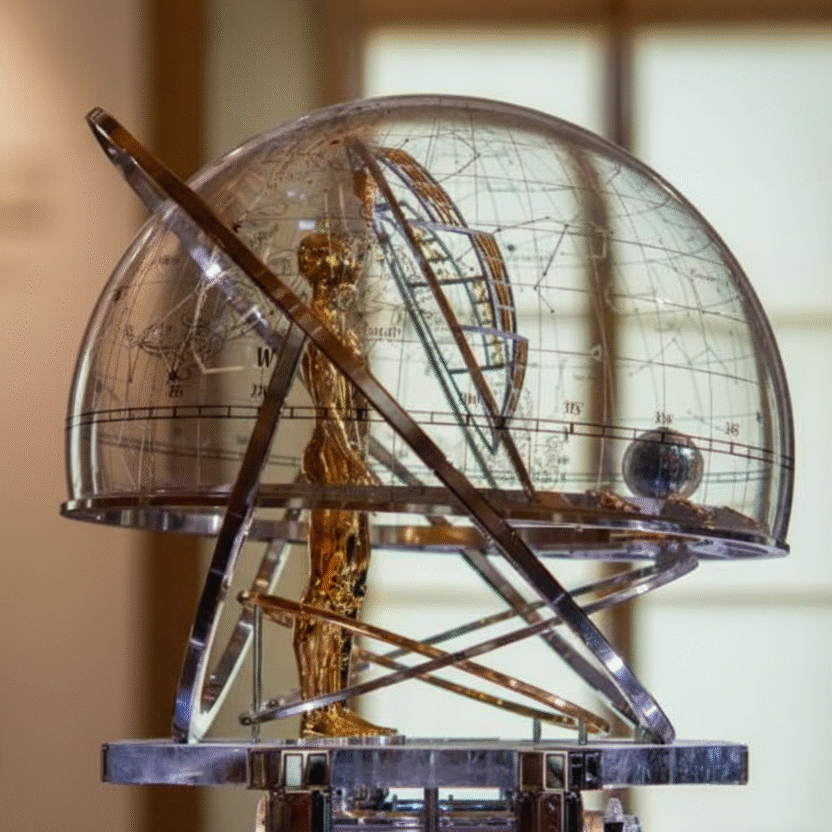

La Québec du Temps, the magnificent astronomical clock that Vacheron Constantin displayed last month, is the focal point of the space.

If you can’t make it, you should still have a look at the amazing items on exhibit, which are arranged chronologically.

A piece of an Egyptian Clepsydra, circa 332–30 BC

The oldest clock on display is about 2,300 years old, decades before mechanical clocks. Its state is explained by its antiquity; all that’s left of an ancient Egyptian clepsydra, or water clock, is a small shard. The fundamental technology used in the construction of this water clock dates back hundreds of years. Experts estimate that this kind of clepsydra could measure time to within about 15 minutes per day, accurate enough for use in practical, ceremonial, or astronomical contexts. The device was essentially a flat-bottomed vessel with a hole drilled precisely so that water would leak out at a predictable rate.

The vessel’s interior was marked with concentric circles to represent the hours and, in order to keep with the seasons, distinct marks for each of the year’s twelve months.

A portion of an automated clock shaped like a peacock Cordoba, around 962 or 972

The exhibit’s second-oldest clock is a fragment that is thought to have been a part of a crude mechanical clock constructed for the Caliph’s court in Córdoba, Spain, in the tenth century. It is thought to have been a component of a mechanical peacock that would drop pellets from its mouth to indicate the hours because it resembles other known Hellenistic clocks of this kind. Similar to crown jewels, these objects were used in courtly settings to show the ruler’s strength and divine authority. Its artistic shape serves as another reminder of how closely design and ornamentation have been linked to horology since its inception.

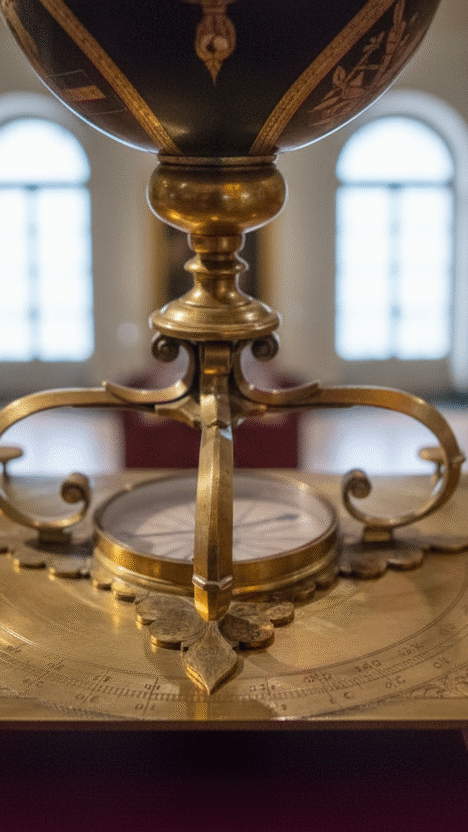

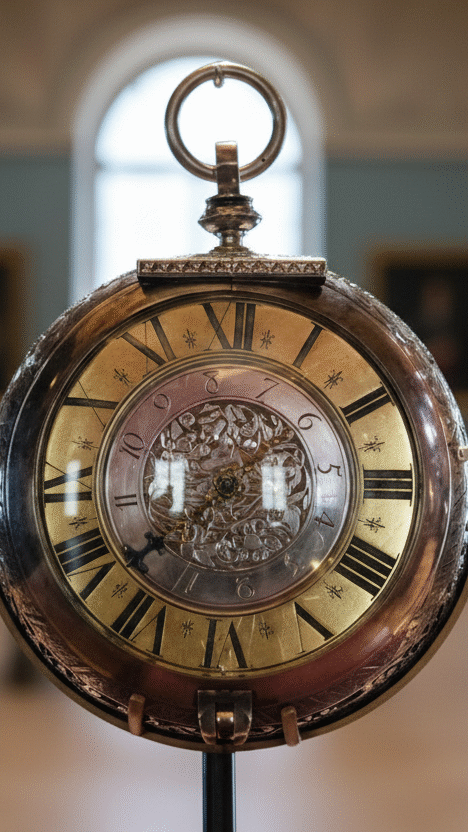

Spherical Timepiece

Blois, Jacques de la Garde, 1551

The third clock in the display is from the 16th century, when the first portable spring-driven clocks appeared. The spherical watch on exhibit was manufactured in Blois in 1551. making it the one of the oldest known French made watches bearing both a signature and a date.

It was a crude, one handed gadget that was undoubtedly incredibly inaccurate by today’s standards, but it was the most advanced technology available at the time. Similar to how haute horlogerie wristwatches are used now, a watch like this would have served as a social status indicator.

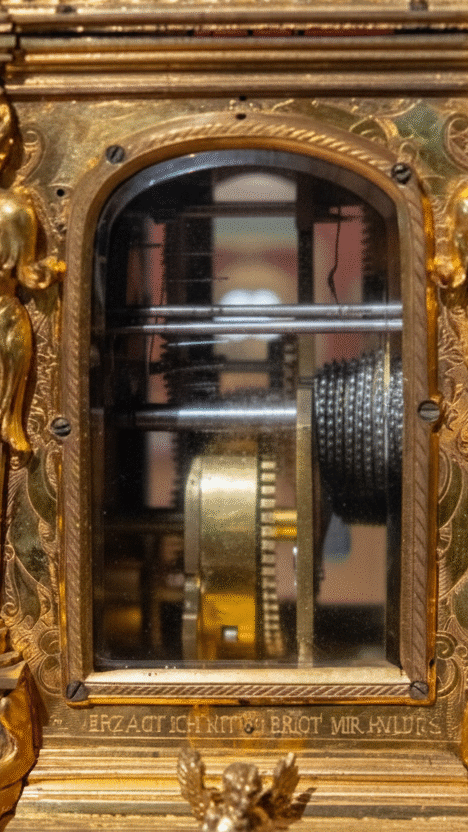

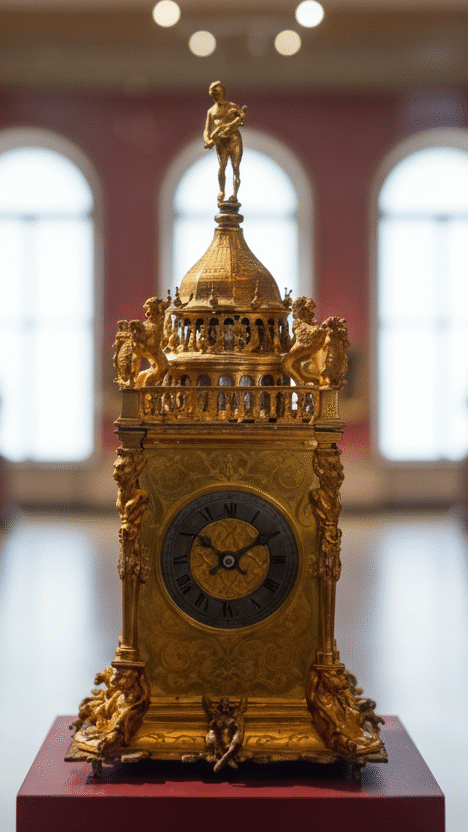

Table Clock in the Shape of a Square Tower

Germany, late 16th century

For as long as there have been clocks and watches, the wealthy and influential have sought for or commissioned unique designs to indicate their social standing. Such a clock, modelled after a fortified tower and adorned with the coat of arms of the influential Farnese family of Parma, Italy, is the fourth item on exhibit.

The brass, bronze, and silver clock was most likely manufactured soon after Jacques de la Garde’s spherical watch. To convey the owner’s authority and sense of style, it is elaborately ornamented from top to bottom. An allegory of justice is etched on the back of the clock, most likely to support the Farnese family’s superior status in society.