A Novel Perspective on the Wandering Hours by H. Moser & Cie.

With the Pioneer Flying Hours, a fresh approach to the wandering hours, Schaffhausen based H. Moser & Cie. revisits a challenge it previously provided. While the hours appear to move from one window to the next, the watch displays the minutes on a central ring. The Flying Hours may be one of the most fascinating leaping hours available because to this amazing new presentation.

The Pioneer Flying Hours is not Moser's first attempt at the wandering hours; the Endeavour Flying Hours, an update on the historical complexity, was introduced about seven years ago. But with the darting, roving display of the new Pioneer, Moser is able to convey the mystique of both early wandering hours and secret clocks.

Collectors will undoubtedly enjoy this neat and, to be honest, unique reimagining of the wandering hours. The minutes scale's continuous movement over shuttered apertures has a poetic quality; its sweep resembles a bridge between points in time, depicted spatially in this instance.

The wandering hours, which are typically a problem linked with more formal, small cases, are particularly peculiar when combined with the sporty, spacious Pioneer case. Even for a sports watch, the size is big at over 43 mm. To be picky, if anything is offensive right away, that's the name. In technical terms, "Flying hours" refers to a rotating platform that is only supported from below, analogous to a flying tourbillon. Only the minute scale is visible on the dial, while the hour discs and gear mechanism are buried beneath it.

The updated complication

The kind of useless but charming complexity that makes mechanical timepieces intriguing and alluring is the wandering hours. Clocks, pocket watches, and wristwatches from well-known brands like Audemars Piguet as well as independent designers like F. P. Journe are examples of the eccentric time-telling format's ongoing appeal.

This Pioneer Flying Hours line's use of the "flying" complexity is its most intriguing feature. Most wandering hours, like the Audemars Piguet Starwheel, have a carousel that slowly revolves around the dial with the hours disc pointing to a minutes' sector. The hours disc is gradually indexed to the next place as the hour goes on thanks to the engagement of fixed fingers and hidden star wheels. Timekeeping itself may be impacted during this somewhat gradual adjustment because the process is not immediate and is relatively torque-intensive.

Moser chose to hide the hour discs and just show the current hour through dial apertures with the Pioneer Flying Hours, doing away with this slow-moving rotating spectacle. Moser also managed to jump from one hour to the next, giving the impression that the change happened instantly.

It's interesting to note that while one of the apertures shows the current hour, the other two are hidden by a kind of shutter, which could be the trick behind Moser's "instant" hour shift. Although further information is not yet available, it is possible that the shutter snaps instantly as the hour changes, but the hour discs shift at the same sluggish pace as they did in the Endeavour model. Consequently, the shutter piece hides the hour disc indexing as well as the only the current hour visible.

The centre minutes sector reads the minutes against the "active" aperture, which displays the current hour, as it sweeps the dial, completing a complete rotation every three hours. The shutter advances when the hour changes, the minutes sector now reads against it, and the next aperture in a clockwise manner indicates the hour, making it "active."

Aventurine dial

Although the sophisticated complication may seem a bit out of place in the sporty Pioneer case with a 120-meter rating, the Pioneer Flying Hours makes its premiere in two well-made models. There are only 100 of the rose gold example with a sci-fi theme. It features a glass product called aventurine with artificially added metallic particles. Each piece has a distinct midnight speckled-sky appearance as a result.

Sturdy motion

Moser's internal automatic HMC 240 powers the Flying Hours. The movement, which aims for more contemporary styles across its calibre range, is in line with Moser's latest attitude. With flawless machine finishing put over the anthracite-colored bridges, Moser does not let us down in terms of finishing. A minor shift towards increased production is also shown in the movement. Although Moser's previous internal calibres had exceptional regulating organs and double barrel topologies, the current trend is towards more uniform construction.

The wandering hours module is based on the HMC 201 calibre, making the HMC 240 a modular movement. The 3 Hz movement's bi-directional winding rotor allows it to retain 72 hours of power reserve on a single barrel. The majority of the escapement and going train are visible due to the caliber's heavy yet elegant skeletonization. A flat Straumann hairspring manufactured by Precision Engineering is used in conjunction with the free-sprung balance. Given that this is intended to be a sports watch, the full balance bridge is a great feature.

When Design Met Destiny: Gérald Genta, Credor, and the Watch That Defined Two Worlds

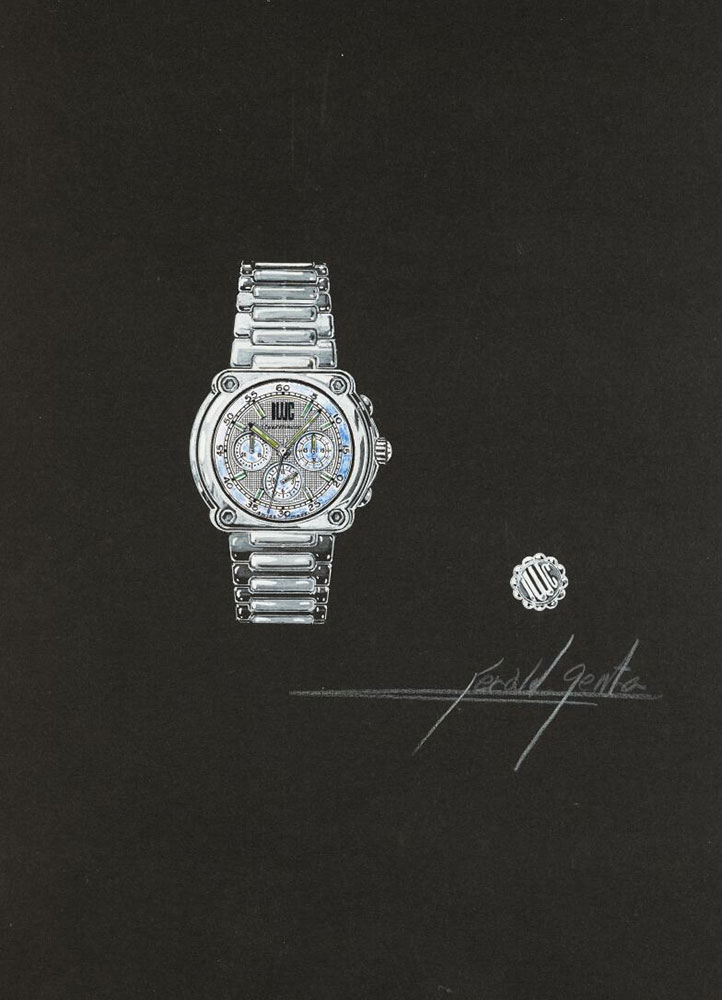

Few designers have had as much of an impact on contemporary watchmaking as Gérald Genta, yet few of his designs are as intimately revealing of his brilliance as the Credor Locomotive. It was a moment of rebirth, when the Swiss maestro who had transformed the Royal Oak and Nautilus at last found his own voice, long before it was reinvented in titanium for the twenty-first century.

Genta saw inspiration rather than competition in 1979, when a large portion of the Swiss watch industry looked at Japan with cautious curiosity. One of the most significant changes in his career would be sparked by his collaboration with Reijirō Hattori, the grandson of Seiko's founder. He received something far more than just another design brief from the project, a watch commissioned for Seiko's luxury brand, Credor. It boosted his self-esteem.

That romance changed everything, according to his wife and collaborator for life, Evelyne Genta. She remembers that "Mr. Hattori told Gérald to stop hiding behind other brands and put his own name on a watch." He did not view him as a supply, but as an artist. At that point, he also started to perceive himself in that light.

A Design Without Boundaries

Genta had never made anything like the Credor Locomotive. The Locomotive represented something more subdued, a dialogue between two cultures equally fixated on accuracy and perfection, whilst the Royal Oak represented industrial charm and the Nautilus oceanic elegance. Its hexagonal bezel took the place of Genta's trademark octagon, which is uncommon in his repertory. The shape was intentional; it was a reference to Japanese geometry, which combines angular strength and circular balance. Its dial's honeycomb design, which was accentuated by opposing light reflections, created the poetic illusion of color transitions within a single shade, echoing Japanese minimalism.

His profound grasp of structure was demonstrated by the intricate and architectural bracelet. Genta had began his work as a bracelet designer at Gay Frères, and he viewed metal like sculpture , creating tension, proportion, and harmony from what others perceived as mechanics. Each screw and edge had a purpose. Nothing was decorative, yet every surface conveyed peaceful luxury. Evelyne claims that "you can see his mind working when you look at the Locomotive." It is not a bracelet watch, but it is an integrated one. Like a musical breath between notes, the negative space between the case and the bracelet gives it rhythm.

A Partnership That Changed Watchmaking

For Genta, Japan was a discovery rather than a rival. He refused to give in to nostalgia during the height of the Quartz Crisis, when Swiss workshops closed and mechanical movements appeared to be outdated. He turned his gaze to the East, to a society that valued artistry and flaws as components of beauty. Evelyne muses, "Gérald loved the way the Japanese used gold to fix broken things." "He saw in that philosophy the same truth that time and touch give value, just like in watchmaking."

The encounter between Hattori and Genta served as the catalyst for his eventual independence. He will soon introduce his own brand, which was practically unimaginable in a traditional market where designers were hidden behind maison names. In retrospect, the locomotive served as a link between two worlds: Swiss creativity and Japanese discipline, as well as between personal growth and prior accomplishment.

A Legacy Revived

Evelyne Genta gave her immediate approval when Credor made the decision to bring the Locomotive back to life decades later. With its deep forest-green dial and high-intensity titanium construction, the 2025 edition honors Genta's iconic dimensions of 38.8mm across and an incredibly compact 8.9mm. Its honeycomb dial, which is made up of alternate grooves, moves with the light like silk. According to Evelyne, "the design feels alive." "Gérald would have loved the human touch, the patience, and the accuracy." It is an ideal continuation of his beliefs.

In a society that is frequently dominated by hype and algorithms, Genta's worldview is still relevant today. He felt that no machine could replicate the warmth of human labor, and that true beauty necessitated imperfection. "He didn't have a fear of technology," Evelyne says quietly. “He just knew it couldn’t replace feeling.”

The Art of Time

The Credor Locomotive is still regarded as one of Gérald Genta's most intimate works, not because it was his most daring or well-known design, but rather because it perfectly encapsulated his metamorphosis. In a world that was changing all around him, it symbolizes a designer breaking free from the brands he had established and discovering his own rhythm.

In every way, it is a watch between the East and the West, between engineering and art, between genius and humility.

Evelyne states, "I feel optimistic when I wear it, the same feeling Gérald had when he drew it for the first time." It serves as a reminder that beauty simply takes on new forms and never truly goes away.

"Shahnameh" Tribute Enamel by Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso

A thousand years of Persian art, revived on the wrist.

One of the oldest epic poems in the world is turned into wearable art with the Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso Tribute Enamel "Shahnameh," a poetic fusion of horology and tradition. The Reverso has long served as a blank canvas for tiny enamel painting because of its flip cover and plain back. In this four-part series, Jaeger-LeCoultre (JLC) honors Ferdowsi's 11th-century Persian literary classic, the Shahnameh, also known as the "Book of Kings."

The pictures in the collection were commissioned in the 16th century by Shah Tahmasp, the second Safavid dynasty king. More than 250 paintings were previously included in that fabled text, which took 20 years to finish and is called The Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp. Its vivid colors, intricate representations of myth, and celebration of royal virtue continue to make it one of the best specimens of Persian miniature painting, despite being dispersed throughout museums today.

The Canvas on the Reverso

The Reverso was first designed in 1931 for British officers in India who needed to shield their watch crystals during polo tournaments. Since then, it has undergone significant change. Today, its rotating case acts as a link between great art and horology. One of the few watchmakers with an enameling workshop on-site, Jaeger-LeCoultre, has honored artists from Monet to Van Gogh using this format. However, the "Shahnameh" editions represent a significant cultural change, shifting the focus from Europe to the Middle East, the birthplace of polo.

The four white-gold timepieces in this limited edition each have a unique enamel miniature that portrays well-known Persian mythological scenes on the back:

- Siyavush Plays Polo before Afrasiyab

- Faridun Tests His Sons

- Saam Comes to Mount Alburz

- Rustam Pursues Akvan

The Persian epic's moral drama and vivid storytelling are brought to life in these pieces, which were created by JLC's master enamellers utilizing ancient Grand Feu techniques. The dials, on the other hand, are tastefully simple and feature flinqué enamel, which is a coating of translucent enamel put over a guilloché basis.

Detail and Craftsmanship

Each Reverso "Shahnameh" is housed in the iconic Grande Taille white-gold case and measures 45.6 mm by 27.4 mm with a thin height of 9.73 mm. The Calibre 822, a hand-wound movement made especially for the rectangular shape of the Reverso, beats inside. With a 42-hour power reserve and a sophisticated design that accentuates the understated elegance of the front dial, the movement, which was first introduced in 1991, continues to set the standard for dependability and simplicity.

Although the front dials vary slightly, some have a lozenge design in forest tones, while others have wave guilloché in sea green, all of them stick to the simple, Art Deco proportions that characterize the Reverso line. These fronts provide understated elegance, guaranteeing that the enamel painting that is exposed when the case is turned over stays the primary attraction.

Tales in Enamel

The narrative depth of two of the four timepieces is particularly noteworthy. In "Saam Comes to Mount Alburz," the prince makes a comeback to retrieve Zal, his albino son, whom he had left behind due to superstition. Perched above the mountains in the scene is the legendary Simurgh, a knowledgeable and kind bird that reared Zal and represents atonement and divine direction. Its sweeping fluidity and jewel-like hue are captured in JLC's replica of the original folio, which is housed in Berlin's Museum of Islamic Art. The Persian hero is shown fighting a horned demon that can transform into a onager (wild donkey) in "Rustam Pursues Akvan," which is currently housed in the Aga Khan Museum collection. Rustam defeats the demon by tricking him with cunning and might, a classic example of intellect triumphing over force. From the twisted corpses to the elaborate Persian designs enclosing the scene, every brushstroke on the enamel surface evokes tension and action.

Art on the Wrist

Even while the dials are beautiful, they might not have the same transcendence as the small enameling on the reverses, which reaches almost museum level. Reviewers pointed out little variations in the flinqué enamel's clarity on the prototypes; they will probably be fixed in the finished product. Nevertheless, these timepieces rank among the best métiers d'art in contemporary horology due to their entire execution. The Reverso Tribute Enamel “Shahnameh” reaches rarefied status for over $142,000 USD per. The cost, however, is a reflection of both the historic value of preserving Persian art in Swiss craftsmanship as well as the hours of hand painting needed for each dial.

A Gathering of Civilizations

These timepieces are more than just rarities; they are a meeting of two traditions: Persian poetry and Swiss precision. The "Shahnameh" Reverso shows how the language of art is not limited by time or place. For collectors, it provides a material connection to a thousand years of storytelling, encapsulated in enamel, gold, and fire; for Jaeger-LeCoultre, it is a contemplative recognition of the worldwide legacy that informs contemporary luxury. The Reverso Tribute Enamel "Shahnameh" challenges us to stop, flip the page, rediscover history, and realize that time itself may be a work of art in a world that goes quickly.

Richard Mille RM 63-02 Worldtimer: A Novel Approach to Travel Time

Richard Mille's most recent invention, the RM 63-02 Worldtimer, is one of the few watches that successfully blends intricacy, functionality, and spectacle. A 47 mm pink gold and titanium case encircling a bezel-controlled global time mechanism that transforms geography into performance art is the latest aesthetic spin on one of the brand's most intricate travel complexities.

A world of machines at your fingertips

Despite the fact that daylight savings and half-hour time zones frequently undermine their accuracy, world time watches have long offered a romantic connection to the world traveler. The RM 63-02 uses mechanical creativity to overcome the flaw. To switch between cities, the wearer just spins the bezel rather than using a crown or pushers. With each click, the 24-hour ring, date, and hour hand move in unison, driven by a planetary differential that converts the action of the bezel into mechanical time movements.

It's a sophisticated idea carried out with the audacity that defines Richard Mille. 24 cities representing different time zones are displayed on the rotating bezel; the city that is at 12 o'clock is designated as "home." A tiny mechanical theater that transforms jet-lag management into something enjoyable is the bezel, which can be turned counterclockwise to instantaneously change the local time

Architecture of motion

The CRMA4 calibre, a proprietary movement with a rose-gold rotor and almost 34 mm across, is housed inside the RM 63-02. It is composed of titanium plates and bridges coated with titanium. Strong chronometric performance is ensured by its 4 Hz oscillating free-sprung balance. Similar to Greubel Forsey, the action maintains power and precision by reducing internal friction through a fast-rotating barrel.

Although futuristic designs and cutting-edge materials are frequently linked to Richard Mille watches, the execution of this model is unexpectedly elegant. The case, which has more than 100 separate components, varies between brushed titanium and polished rose gold to provide warmth and technical contrast. A wearable paradox for such a commanding watch is that, despite its enormous 47 mm diameter, the brand's iconic curving case back fits snugly around the wrist at 14 mm.

Form meets function

Skeletonized bridges, brilliant pink accents, and bold dauphine hands with diamond-cut bevels and pink Super-Lumi Nova are just a few of the layers that make up the sapphire crystal dial. When changing time zones, the double-disk date display at 12 o'clock advances automatically, but it may also be independently adjusted using the pusher at 10 o'clock. In homage to automotive design, a selector button beneath the crown alternates between winding, neutral, and hand-setting modes; however, the latter halts the seconds, an inevitable trade-off in an otherwise fluid system.

Engineering beauty

Technical coherence is preferred over traditional hand-finishing in Richard Mille's finishing concept. Clean industrial surfaces, obvious gemstones, and machined geometry that feels more aeronautical than handcrafted are all characteristics of RM 63-02 that embody that philosophy. Under magnification, even minor flaws, such obvious machine marks, appear intentional and are in line with a company that values innovation over refinement.

The luxury of mobility

Richard Mille's RM 63-02 World timer, which is limited to 100 pieces, is bold, over-engineered, and surprisingly wearable. Although its 30-meter water resistance may prevent it from being on the diving list, it makes time-zone adjustment haptic for both collectors and frequent travelers. The RM 63-02 is ultimately more about celebrating motion than it is about tracking global hours. It is a mechanical passport for a world that still prioritizes craftsmanship over convenience and demonstrates that, even in the digital age, the art of timekeeping can still cause you to stop, think, and be amazed.

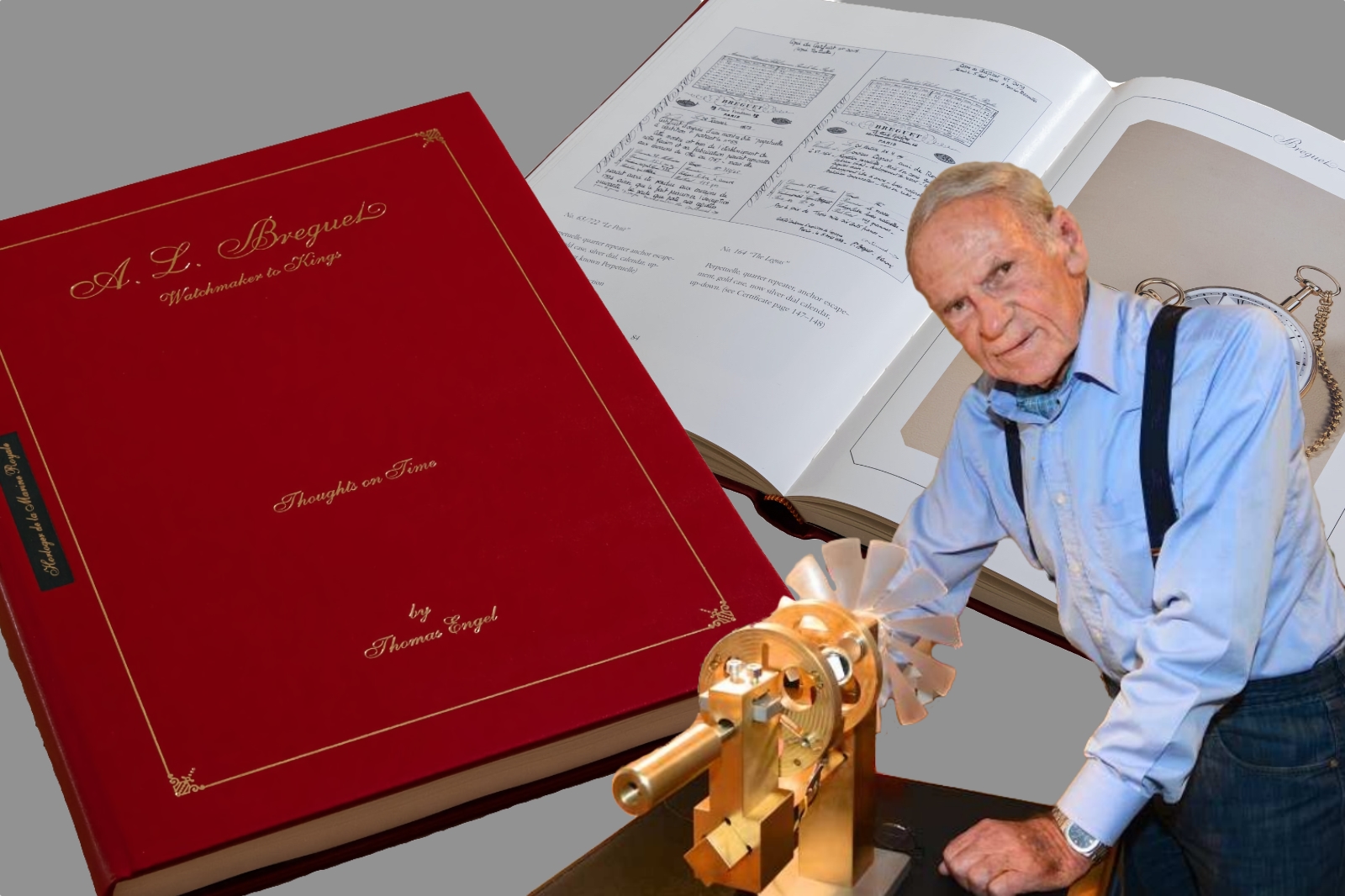

The Inventor Behind the World’s Most Scholarly Watch Collection

Thomas Engel gathered information to comprehend, not to impress. He had already secured more than a hundred patents, learned himself polymer science from library books, and established a profession based solely on self-discipline before watches captured his interest. He carried the same systematic mentality that had once transformed plastic buckets into an industrial empire with him when he finally turned to horology.

Engel was born in Leipzig in 1927 and grew up in a war-torn and loss-ravaged Germany. His early years required him to be resourceful; he exchanged items, sold pigeon feed, and discovered that opportunity and observation were just as important to survival. Lacking formal education, he discovered a store in Frankfurt that sold buckets coated in plastic for 10 dollars each after the war. He spent nights studying plastics at the local library because he was so perplexed by the price. By the time he was forty, he had become a millionaire after inventing a new technique for cross-linked polyethylene (PEX) and licensing it globally in a matter of years.

He was defined by his independence. He turned down corporate offers and worked from his farm near Frankfurt, which had a private lab and heliport. Later, his collection was guided by the same drive. The discovery that his first watch, a purported Breguet, was a fake may have demoralized others, but it ignited his lifelong fixation with authenticity. Under the influence of sellers like Edgar Mannheimer and collectors like Cyril Rosedale, Engel evolved from an inquisitive consumer into an academic. He discovered that true connoisseurship entailed being aware of a watch's provenance, story, and mechanism in addition to its price.

He established a quiet but commanding presence in Zurich and London auction halls. Through coded nudges under the table, his partner Mannheimer would bid on Engel's behalf, enabling him to covertly purchase classics like as tact watches, repeaters, and tourbillons. When the throng thinned at another sale, he bought a whole catalogue of Breguet watches, and once outbid the British Museum for a rare Breguet with jumping seconds. However, the verification was more important to him than the triumph. Each component was measured, photographed, recorded, and compared to Breguet's ledgers in an experiment.

Engel valued innovation over ornamentation. He was attracted to souscription watches for their clarity, garde-temps chronometers for their scientific accuracy, and the tourbillon for its function rather than its beauty. He saw every mechanism as a solution to an issue and a link between engineering and art. Convinced that timepieces, like patents, could use mechanical logic to reveal human development, he documented every technical and historical detail.

Engel put his study into paper after his ambitions to open a museum in Germany fell through. In the field of watch research, his 1994 book Breguet: Thoughts on Time became a seminal work. It altered how dealers and auction houses explained provenance and technical craftsmanship by fusing personal ideology with catalog information. Engel's claim that "one cannot improve on a Breguet" became a collector's creed after he likened Breguet's genius to Stradivarius on the basis of inventiveness rather than perfection.

Engel eventually made it difficult to distinguish between maker and collector. He collaborated with Zenith and Swiss watchmaker Richard Daners to create a limited line of tourbillons and regulators under his own brand, all of which were constructed to his precise specifications. He saw signing a watch as a last experiment in which he once again became the inventor, not a sign of vanity.

Even though Thomas Engel passed away in 2015, his impact lives on. His approaches changed the way history is written through artifacts, provenance is examined, and authenticity is confirmed. He demonstrated that collecting could be an intellectual activity rather than a luxury and that each tick of a Breguet conveys testimony in addition to time. After all, Engel's greatest creation was a method of thinking that was exacting, inquisitive, and ageless rather than a polymer or a watch.

Geneva Spring Auctions 2025: Tradition, Taste, and a Touch of Surprise

People, prices, and perfection in a shifting market.

The 2025 Geneva spring auction season produced a collection of solid, albeit inconsistent, performances despite economic concerns, significant currency volatility, and changing collector trends. With a few notable events and a few surprising results, the four big houses, Phillips, Christie's, Antiquorum, and Sotheby's, collectively demonstrated that fine watch collecting is still strong.

Phillips: Risks and Rewards

With less than 200 lots and CHF 43.4 million, Phillips was the obvious winner. Although its catalog took a chance by including pocket watches and clocks that weren't part of the popular wristwatch sector, the gamble paid off handsomely. The Breguet Sympathique No. 1, the season's best-selling piece, brought CHF 5.51 million, confirming the company's readiness to support both modern and historical watchmaking. Unusual items also saw good sales at Phillips, including a 1918 Charles Frodsham carriage clock that brought CHF 812,800 and the Cartier portico mystery clock No. 3, which brought CHF 3.93 million. These findings highlight a growing collecting community that is more interested in mechanical talent and provenance than just hype.

Christie’s: Classic but Competitive

Christie's, which offered a more conventional collection interspersed with jaw-dropping shocks, came next with CHF 21.2 million in total sales. A Richard Mille RM UP-01 Ferrari's hammer price of CHF 736,000 was matched by the Cartier Crash "NSO," a stunning replica with a unique nickel-grey dial. The contrast between the two watches aptly captures the current market: one is praised for its engineering and exclusivity, while the other is praised for its design and mystique. However, visual storytelling, works that take stunning photos and flourish on social media, where popularity frequently starts, was largely responsible for both of their success.

Antiquorum and Sotheby’s: The Specialists

Sotheby's and Antiquorum: With over 800 lots available, the Specialists Antiquorum made CHF 10 million. Its inventory was more accessible and broader, but the most notable item was a Breguet pendule à almanach, a magnificent carriage clock that was originally owned by Russian aristocrats and brought CHF 1.25 million. In contrast, Sotheby's ended at CHF 6.75 million, in part because its top lot, a rare platinum Rolex Daytona "Zenith" with a mother-of-pearl dial, was withdrawn. Sotheby's total could have increased by a third if it had sold.

Journe: The Collector as Curator

The season's most significant purchaser was none other than the legendary F.P. Journe. For his soon-to-open museum in Geneva, the independent watchmaker acquired the Breguet pendule à almanach as well as the Breguet Sympathique No. 1. His purchases, which came to a total of CHF 6.76 million and represented almost 8% of the season's total sales, demonstrate Journe's continued status as a maker and keeper of horological history. After the sale, he said, "It is crucial for my museum," emphasizing that some watches go beyond collecting to become part of cultural preservation.

Market Currents and Collector Behavior

While top pieces achieved extraordinary achievements, the broader market exhibited symptoms of discerning. Prices for independent manufacturers like Roger W. Smith decreased; a Series 1 that sold for CHF 730,000 in 2023 now only brought in CHF 355,000. Vintage categories, too, required near-mint condition to attract bids, “new old stock” models commanded premiums, while restored examples often failed to reach projections.

Visually attractive modern timepieces, on the other hand, became increasingly popular. At Phillips, the F.P. Journe Tourbillon Souverain "Coeur de Rubis" opened to intense bidding and sold for CHF 1.63 million, exceeding all expectations. The Cartier Crash at Christie's generated similar enthusiasm, proving that price and taste are still influenced by rarity and recognizability, even in the Instagram age.

A Season of Paradox

The Geneva auctions in spring 2025 were paradoxical: collectors wavered between novelty and history, clocks and wristwatches, and visual flair and technical depth. Under the show, a distinct pattern became apparent: provenance and perfection continue to be paramount. Buyers demonstrated a willingness to spend for quality, authenticity, and story, whether it was a centuries-old Breguet finding a new home or a flawless Vacheron Constantin ref. 6448 minute repeater in platinum selling for CHF 698,500.

Geneva has again reminded the world that, at its core, exquisite watchmaking is still a human art, motivated by passion, expertise, and the pursuit of time made palpable, in an era dominated by algorithms and aesthetics.

Observations and Takeaways at Watches & Wonders 2025

Watches & Wonders 2025 was, in some ways, the largest event ever. The number of visitors increased by 12% to 55,000 from the previous year, and more annoyingly, hotel room-nights increased by 17% to 43,000, which may help to explain why lodging costs are rising annually (albeit thankfully still far from Basel's extortion).

However, on other metrics, I am certain It was a bad year for Watches & Wonders (W&W). Retailers' orders for new timepieces are undoubtedly lower than they were a year ago. Even before American tariffs were announced midway through the fair, there was a general sense of unease. However, as is frequently the case, most executives expect their brand will outperform because it is superior, even though they admit a slowdown.

Big And Small Brands

The level of innovation at major brands in contrast to independent watchmakers is one of the most intriguing trends this year. The F.P. Journe FFC from two years ago is one of the all-time greats; historically, indies have tended to have the more noteworthy productions, but this year was different.

The Rolex Land-Dweller and the Vacheron Constantin Solaria Ultra Grand Complication were the two finest W&W season debuts from major brands (or at least an established brand owned by a large group). The Land Dweller's cal. 7135 combines an astounding amount of improvements, while the Solaria is the most intricate wristwatch ever created. Crucially, it earned the distinction thanks to a skilfully designed movement that maintains its compact size.

At 45 mm by 14.99 mm high, the Solaria is perhaps the most wearable “ultra” grand complication

The G.F.J., a time only wristwatch with a reconstructed cal. 135 observatory chronometer movement, is one example of how independent watchmaking joined the trend. Independent watchmaking, on the other hand, was all about the flavour of the day, which is a time only watch with a highly decorated movement, usually without a dial and instead the mechanics exposed on the face.

The movement inside the Zenith G.F.J. is essentially a replica of the cal. 135, with a few improvements

Although independent watchmakers used to frequently do their own thing, their success has been greatly attributed to their understanding of contemporary tastes. In the hopes that the watchmaker will become the next Francois Paul Journe, many aficionados are willing to deposit money for deliveries several years in the future, demonstrating the tremendous demand these independent watchmakers possess. Crucially, though, a few newcomers showed out in this field, such as AHCI candidate Dann Phimphrachanh, who worked with Raul Pages at Parmigiani. His art is excellent and has potential even though it is still in three hand format.

Watches…

The Rolex Land-Dweller is unquestionably the most significant watch debut of 2025. Its cal. 7135 inside which lacks a natural escapement makes it significant, not the band or its style. Our review of the watch and its movement contains all the information you need to understand why it is revolutionary. In my opinion, the Land-Dweller in Rolesor is a simple purchase; nevertheless, the platinum is the best option but takes a significant financial investment. The Lange Minute Repeater Perpetual is less inventive yet perfectly represents its creator. The Minute Repeater Perpetual, which is essentially a hybrid of the Langematik Perpetual and Richard Lange repeater, is made with the superb craftsmanship that distinguishes Lange timepieces.

Mechanical Wonders at the Louvre, From Ancient Egypt to Vacheron Constantin

Mécaniques d'art, which opened on September 17th to commemorate the 270th anniversary of Vacheron Constantin, the museum's philanthropic partner, is an exhibition at the Louvre dedicated to mechanical art objects, specifically ten historically significant clocks and watches (though some of the oldest are only fragments).

The exhibit, on display in the Sully wing until November 12th, shines a welcome light on an often-overlooked aspect of the museum's decorative arts collection; pieces that merge technical expertise with mankind's obsessive quest to measure time and explain the heavenly bodies.

La Québec du Temps, the magnificent astronomical clock that Vacheron Constantin displayed last month, is the focal point of the space.

If you can't make it, you should still have a look at the amazing items on exhibit, which are arranged chronologically.

A piece of an Egyptian Clepsydra, circa 332–30 BC

The oldest clock on display is about 2,300 years old, decades before mechanical clocks. Its state is explained by its antiquity; all that's left of an ancient Egyptian clepsydra, or water clock, is a small shard. The fundamental technology used in the construction of this water clock dates back hundreds of years. Experts estimate that this kind of clepsydra could measure time to within about 15 minutes per day, accurate enough for use in practical, ceremonial, or astronomical contexts. The device was essentially a flat-bottomed vessel with a hole drilled precisely so that water would leak out at a predictable rate.

The vessel's interior was marked with concentric circles to represent the hours and, in order to keep with the seasons, distinct marks for each of the year's twelve months.

A portion of an automated clock shaped like a peacock Cordoba, around 962 or 972

The exhibit's second-oldest clock is a fragment that is thought to have been a part of a crude mechanical clock constructed for the Caliph's court in Córdoba, Spain, in the tenth century. It is thought to have been a component of a mechanical peacock that would drop pellets from its mouth to indicate the hours because it resembles other known Hellenistic clocks of this kind. Similar to crown jewels, these objects were used in courtly settings to show the ruler's strength and divine authority. Its artistic shape serves as another reminder of how closely design and ornamentation have been linked to horology since its inception.

Spherical Timepiece

Blois, Jacques de la Garde, 1551

The third clock in the display is from the 16th century, when the first portable spring-driven clocks appeared. The spherical watch on exhibit was manufactured in Blois in 1551. making it the one of the oldest known French made watches bearing both a signature and a date.

It was a crude, one handed gadget that was undoubtedly incredibly inaccurate by today's standards, but it was the most advanced technology available at the time. Similar to how haute horlogerie wristwatches are used now, a watch like this would have served as a social status indicator.

Table Clock in the Shape of a Square Tower

Germany, late 16th century

For as long as there have been clocks and watches, the wealthy and influential have sought for or commissioned unique designs to indicate their social standing. Such a clock, modelled after a fortified tower and adorned with the coat of arms of the influential Farnese family of Parma, Italy, is the fourth item on exhibit.

The brass, bronze, and silver clock was most likely manufactured soon after Jacques de la Garde's spherical watch. To convey the owner's authority and sense of style, it is elaborately ornamented from top to bottom. An allegory of justice is etched on the back of the clock, most likely to support the Farnese family's superior status in society.

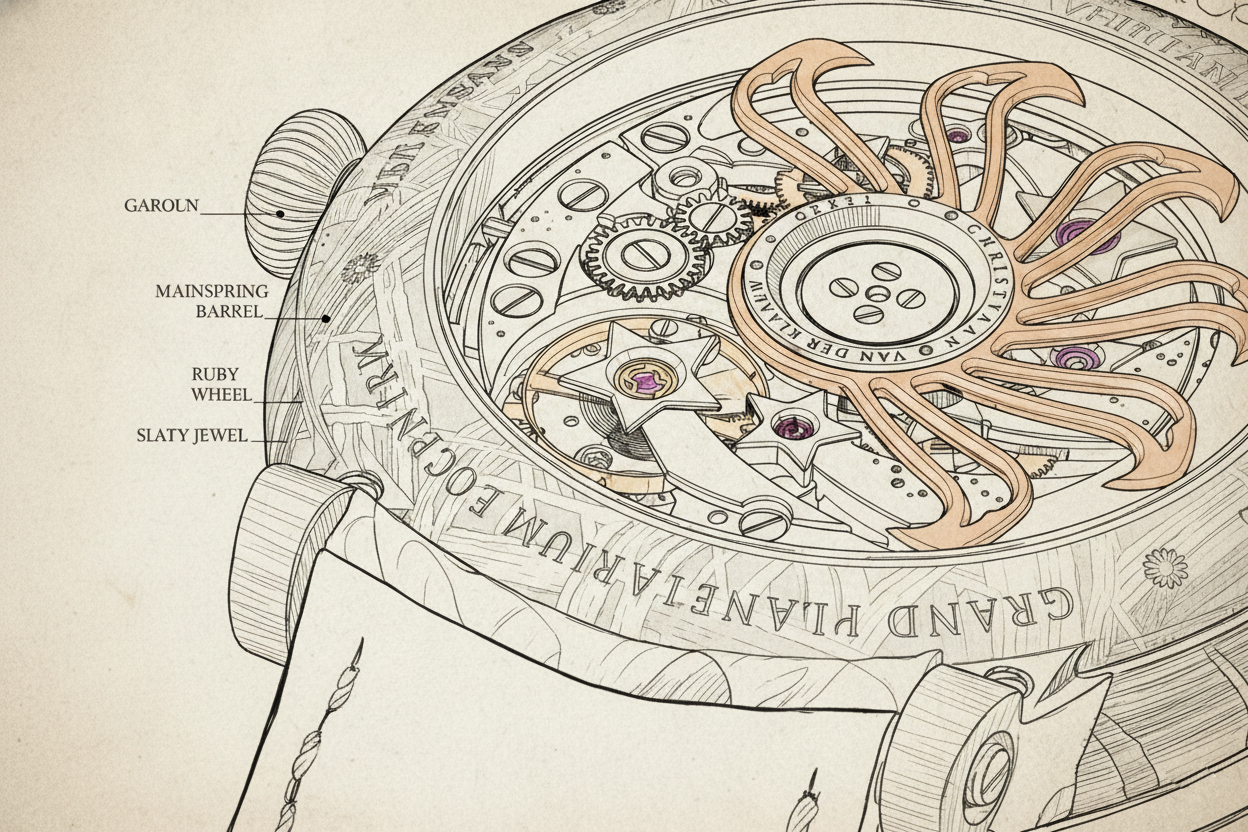

Christiaan van der Klaauw Planetarium Meteorite

The Solar System in Miniature

A timepiece that serves as a reminder of your place in the universe has a subtly humble quality. The Christiaan van der Klaauw Planetarium Meteorite, a cosmic masterpiece from the Dutch atelier that truly puts the solar system on your wrist, is one of the few clocks that perfectly captures that impression.

This is the smallest mechanical planetarium ever made, a poetic device that shows the orbits of Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn around the Sun in real time. It's more than just another astronomical complication. The cosmic idea is carried to its logical conclusion in this special Meteorite edition, where the dial itself is cut from an ancient Muonionalusta meteorite, a fragment older than Earth.

When it comes to planetarium wristwatches, Christiaan van der Klaauw stands almost entirely alone. The Dutch atelier holds much of the intellectual property behind the complication, giving it near-total command over this miniature cosmos of horology. Yet that hasn’t stopped CvdK from one-upping itself. The result is the Grand Planetarium Eccentric Meteorite the most complete representation of our solar system ever placed on a wrist.

Christiaan van der Klaauw is virtually unique when it comes to planetarium timepieces. The Dutch atelier has almost complete control over this tiny universe of horology since it owns much of the intellectual property behind the complication. However, this hasn't stopped CvdK from outperforming itself. The Grand Planetarium Eccentric Meteorite, the most comprehensive depiction of our solar system ever put on a wrist, is the outcome.

Both philosophically and visually, it is an overtly maximalist work of art. The dial is a maelstrom of celestial motion, full of astronomical detail, while the solid 44 mm meteorite case exudes substance and character. This new Meteorite version, which builds on the Grand Planetarium Eccentric that debuted in 2024, takes the idea to a cosmic level by adding an asteroid belt that is adorned with fragments of meteorite that once originated from Mars.

Planned as a limited edition of just three pieces, the scarcity of usable meteorite might mean only two will ever be completed making this already otherworldly watch even more elusive.

At the heart of the dial, the Sun serves as a quietly brilliant reminder of motion it’s not just decorative but functional, completing a full rotation once per minute. It’s a subtle but mesmerizing cue that the entire watch, like the cosmos it represents, is alive and in motion.

Initial Thoughts

The planetarium remains one of the most poetic complications in all of watchmaking precisely because of its uselessness. Unlike a chronograph or perpetual calendar, it offers no practical utility only perspective. And yet, that’s what makes it so profoundly human. For millennia, we’ve gazed at the stars, trying to understand our place among them. A watch like the Eccentric Meteorite distills that age-old pursuit into a wrist-sized universe a mechanical reflection of our enduring curiosity.

There’s also something strangely humbling about its cosmic pace. On this dial, Neptune creeps so slowly around the outer edge that even after two decades of wear, it will have barely shifted. The glacial tempo is a reminder of how small and fleeting our own moments are and how beautiful it is that a watch can make us feel that.

Naturally, the raison d’être of the Eccentric Meteorite lies in its dial a breathtaking stage of aventurine glass that hosts a fully realized miniature of our solar system. All eight planets orbit the central hand stack in realistic, eccentric ellipses, their motions a quiet choreography of cosmic mechanics. Beyond simply telling the time and, in a poetic sense, even the date the dial elevates astronomical display into art. Each planet is hand-painted, while the asteroid belt between Jupiter and Saturn is composed of actual Martian meteorite fragments, lending the composition both authenticity and narrative depth.

The most dramatic shift from its predecessor, however, is the 44 mm meteorite case itself. In watchmaking, meteorite is almost always confined to the dial a visual novelty, not a tactile one. Here, it forms the entire body of the watch, turning a celestial relic into wearable sculpture. The result is unexpectedly compelling: despite its otherworldly heft, the case feels surprisingly comfortable on the wrist, and at just over 14 mm thick, it wears with balance and intention. In both size and spirit, the proportions feel exactly as they should grand, but never gratuitous.

eneath all the celestial spectacle beats a movement worthy of its orbit. The planetarium module is driven by the CKM-01, a premium automatic movement crafted in Sirnach by none other than Andreas Strehler. Though this same 3 Hz platform has appeared in the work of other independents, it remains a quietly impressive caliber robust, refined, and boasting a 60-hour power reserve.

Historically, Christiaan van der Klaauw has relied on third-party engines often dependable workhorses like the ETA 2824-2 as the base for its astronomical complications. The use of a movement from Strehler, one of Switzerland’s most respected independent watchmakers, marks a meaningful evolution for the brand. It elevates the Eccentric Meteorite both technically and symbolically, reinforcing its standing not just as a piece of celestial art, but as a bona fide achievement in modern mechanical watchmaking.

Of course, cosmic beauty comes at a cosmic price. The meteorite case and the addition of the asteroid belt don’t just expand the visual universe of the Eccentric Meteorite they also send its price into orbit. At roughly US $725,000, this edition costs nearly three times as much as its 18k rose gold predecessor. On purely rational terms, that premium is difficult to defend. Yet in the rarefied world of Christiaan van der Klaauw, rationality rarely drives desire. With only a handful of examples expected to exist and each containing literal fragments of Mars it’s hard to imagine collectors hesitating for long.

Final Thoughts

The Grand Planetarium Eccentric Meteorite isn’t just another iteration of an existing complication it’s a statement about what independent watchmaking can be when it dreams on a cosmic scale. It doesn’t chase practicality or subtlety; instead, it celebrates humanity’s timeless urge to map the heavens and hold a piece of them in our hands. Between its meteorite case, Martian dust, and the slow dance of its planets, it reminds us that time is vast and that watchmaking, at its best, can still make us feel small in the most wonderful way.

Patek Philippe Star Caliber 2000 Under the Hammer at Sotheby’s Abu Dhabi

The Patek Philippe Star Caliber 2000 stands as a true masterpiece of modern horology a pocket watch that redefined what mechanical ingenuity could achieve. Created to celebrate the dawn of a new millennium, it was once the fourth most complicated timepiece ever made. Yet, beyond its record-breaking complexity, its brilliance lies in the harmony of art, engineering, and imagination that reshaped the very concept of grand complications.

Now, an original complete set of four Star Caliber 2000 watches is set to make history once again. Sotheby’s will offer this exceptional collection at its first ever watch auction in Abu Dhabi this December the first full set ever to appear publicly. A moment destined to captivate the world’s most discerning collectors and horological institutions alike.

The Technical Significance of the Star Caliber 2000

The Patek Philippe Star Caliber 2000 may not have held the title of “the world’s most complicated watch,” but that was never really the point. What makes it extraordinary is how it redefined what mechanical mastery could look like at the turn of the millennium When it launched, the Star Caliber 2000 ranked fourth in the hierarchy of complications following Patek Philippe’s own Caliber 89, the legendary Henry Graves Supercomplication of 1932, and the lesser-known but equally impressive Leroy 01 from 1904. Yet, where others chased complication counts, the Star Caliber 2000 pursued coherence. Every mechanism served a purpose, every display felt deliberate a hallmark of Patek’s philosophy at its most poetic.

Two and a half decades later, it’s been surpassed on paper by newer feats from Vacheron Constantin and Audemars Piguet, but the Star Caliber 2000 remains a reference point a moment when Patek Philippe showed that complexity, when done right, could still feel effortless.

But the Star Caliber 2000 was never meant to be defined by rankings or numbers that kind of scoreboard is, at best, superficial. Its true genius lies in the substance of its innovation. Beneath the gold case lives a suite of groundbreaking mechanisms, protected by six patents four tied to complications and two to ingenious utility systems each representing a genuine leap forward in how watchmakers think about mechanical architecture.

More importantly, the Star Caliber 2000 stands as Patek Philippe’s last great super-complication pocket watch, the final expression of a tradition that stretches back to the Graves era. It remains not just a technical marvel, but a benchmark in modern watchmaking a reminder that true mastery isn’t measured by how many complications you can fit into a case, but by how seamlessly they all come together.

mong the Star Caliber 2000’s many marvels, its grand sonnerie stands out as the most poetic and the most sonorous. The chiming sequence follows the same musical pattern as Big Ben’s legendary bells in London’s Elizabeth Tower, ringing out with five gongs that fill the air with depth and resonance. When activated, the grand sonnerie performs a symphony of time: the quarters strike first, followed by the hours a deliberate inversion of convention. Even the minute repeater plays by its own rules, sounding in a distinct order of quarters, then minutes, then hours a subtle but elegant rethinking of a centuries-old tradition.

Then there’s the watch’s celestial centerpiece the star chart with orbital moonphase, a first of its kind when introduced. This astronomical display tracks the night sky with mesmerizing precision, mapping the stars as seen from Geneva. The concept would later inspire icons like the Sky Moon Tourbillon ref. 5002 and the Celestial ref. 5102, but it all began here with the Star Caliber 2000, where art and astronomy met inside a pocket watch.

A Masterwork Born of Collaboration

“Every great complication is a symphony and the Star Caliber 2000 had its orchestra.”

Like every true masterwork of haute horlogerie, the Star Caliber 2000 was the result of collective genius. Patek Philippe turned to the legendary Jean Pierre Hagmann to craft the cases, each one a study in balance and proportion. The finishing touch came from Christian Thibert, whose meticulous hand-engraving transformed metal into art.

At the bench, Jean-Pierre Musy led the team responsible for assembling and regulating each movement 1,118 components per watch, each polished, adjusted, and harmonized until the entire mechanism sang in perfect mechanical rhythm. It was an achievement that could only be realized through the fusion of experience, precision, and patience.

Details on the Present Lot

Patek Philippe produced just five complete four-watch sets of the Star Caliber 2000, for a total of 20 pieces. One set was crafted entirely in platinum, while the other four were presented in yellow gold, rose gold, white gold, and platinum. Production began with movement number 3’200’001 and concluded with 3’200’020, marking one of the most exclusive limited runs in modern horology.

The set appearing at Sotheby’s Abu Dhabi represents the fifth and final ensemble, comprising movement numbers 3’200’017 to 3’200’020. For collectors, it’s more than an auction lot it’s the closing chapter in Patek Philippe’s era of monumental pocket watch innovation.