The Inventor Behind the World’s Most Scholarly Watch Collection

Thomas Engel gathered information to comprehend, not to impress. He had already secured more than a hundred patents, learned himself polymer science from library books, and established a profession based solely on self-discipline before watches captured his interest. He carried the same systematic mentality that had once transformed plastic buckets into an industrial empire with him when he finally turned to horology.

Engel was born in Leipzig in 1927 and grew up in a war-torn and loss-ravaged Germany. His early years required him to be resourceful; he exchanged items, sold pigeon feed, and discovered that opportunity and observation were just as important to survival. Lacking formal education, he discovered a store in Frankfurt that sold buckets coated in plastic for 10 dollars each after the war. He spent nights studying plastics at the local library because he was so perplexed by the price. By the time he was forty, he had become a millionaire after inventing a new technique for cross-linked polyethylene (PEX) and licensing it globally in a matter of years.

He was defined by his independence. He turned down corporate offers and worked from his farm near Frankfurt, which had a private lab and heliport. Later, his collection was guided by the same drive. The discovery that his first watch, a purported Breguet, was a fake may have demoralized others, but it ignited his lifelong fixation with authenticity. Under the influence of sellers like Edgar Mannheimer and collectors like Cyril Rosedale, Engel evolved from an inquisitive consumer into an academic. He discovered that true connoisseurship entailed being aware of a watch’s provenance, story, and mechanism in addition to its price.

He established a quiet but commanding presence in Zurich and London auction halls. Through coded nudges under the table, his partner Mannheimer would bid on Engel’s behalf, enabling him to covertly purchase classics like as tact watches, repeaters, and tourbillons. When the throng thinned at another sale, he bought a whole catalogue of Breguet watches, and once outbid the British Museum for a rare Breguet with jumping seconds. However, the verification was more important to him than the triumph. Each component was measured, photographed, recorded, and compared to Breguet’s ledgers in an experiment.

Engel valued innovation over ornamentation. He was attracted to souscription watches for their clarity, garde-temps chronometers for their scientific accuracy, and the tourbillon for its function rather than its beauty. He saw every mechanism as a solution to an issue and a link between engineering and art. Convinced that timepieces, like patents, could use mechanical logic to reveal human development, he documented every technical and historical detail.

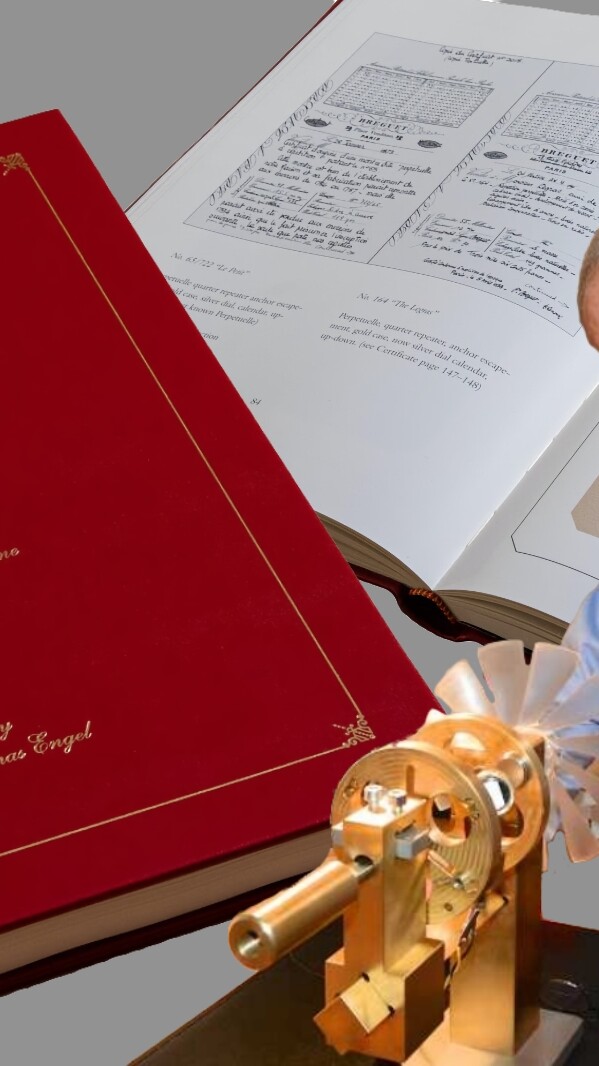

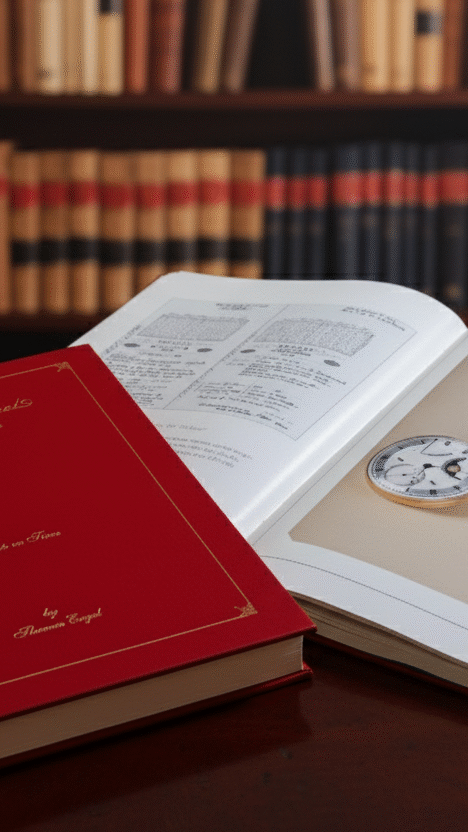

Engel put his study into paper after his ambitions to open a museum in Germany fell through. In the field of watch research, his 1994 book Breguet: Thoughts on Time became a seminal work. It altered how dealers and auction houses explained provenance and technical craftsmanship by fusing personal ideology with catalog information. Engel’s claim that “one cannot improve on a Breguet” became a collector’s creed after he likened Breguet’s genius to Stradivarius on the basis of inventiveness rather than perfection.

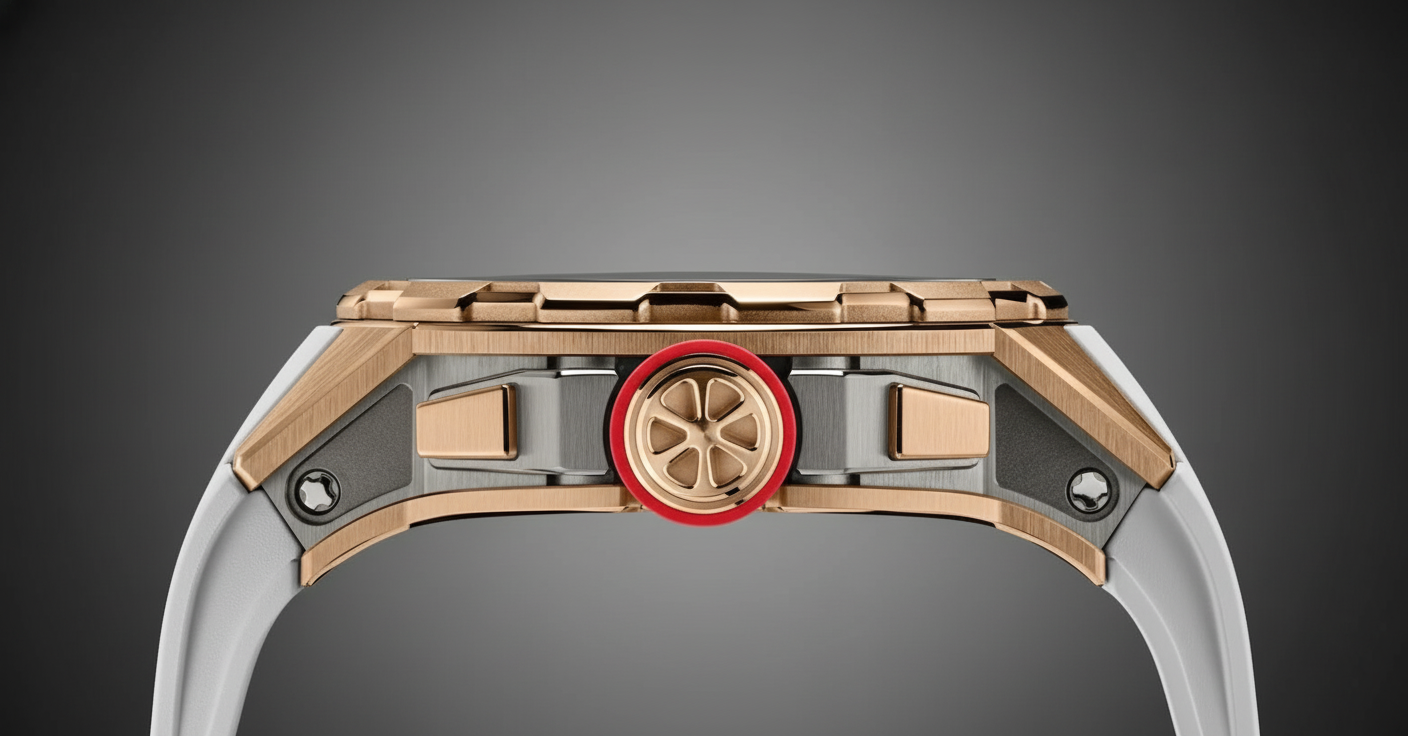

Engel eventually made it difficult to distinguish between maker and collector. He collaborated with Zenith and Swiss watchmaker Richard Daners to create a limited line of tourbillons and regulators under his own brand, all of which were constructed to his precise specifications. He saw signing a watch as a last experiment in which he once again became the inventor, not a sign of vanity.

Even though Thomas Engel passed away in 2015, his impact lives on. His approaches changed the way history is written through artifacts, provenance is examined, and authenticity is confirmed. He demonstrated that collecting could be an intellectual activity rather than a luxury and that each tick of a Breguet conveys testimony in addition to time. After all, Engel’s greatest creation was a method of thinking that was exacting, inquisitive, and ageless rather than a polymer or a watch.